The Intersection of #Ownvoices, Genre Fiction, and Empathy: Guest post by Shaila Patel

In a recent ruling by a Virginia court, five teens (described as two whites and three minorities) were sentenced to read one book a month for an entire year as punishment for defacing a historic black schoolhouse with racist and anti-Semitic graffiti. The books assigned were mostly works of literary fiction with diverse characters and/or racial themes like To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, Night by Elie Wiesel, and Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe.

In a recent ruling by a Virginia court, five teens (described as two whites and three minorities) were sentenced to read one book a month for an entire year as punishment for defacing a historic black schoolhouse with racist and anti-Semitic graffiti. The books assigned were mostly works of literary fiction with diverse characters and/or racial themes like To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, Night by Elie Wiesel, and Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe.

Judging by the conversations I’d seen on the internet, most people thought it was a great idea. I think it’s genius. But could it be taken a step further?

The purpose of the sentence was to impart a lesson in compassion and empathy—the idea that you can put yourself in another person’s shoes and see things from the other person’s perspective. Reading about diverse characters gives these teens the opportunity to realize that even though circumstances and appearances may be different, we’re all the same at heart.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

This is the magical part of storytelling, and what drew me to writing in the first place—the ability to cast readers into a thousand different roles in a thousand different places.

I’m often asked if choosing to make my young adult debut as an #ownvoices novel was intentional, as if they’re really asking whether I’d purposely set out to teach teens a lesson on diversity, empathy, and racial equality. My answer, in case you’re curious, is no. I wrote my Indian-American character Laxshmi Kapadia because it’s what I know. Who better than me, an Indian-American, to show a sliver of what it’s like to grow up straddling both cultures. It’s what the #ownvoices designation is all about—authenticity.

If a teen can relate to an elf going on a quest, they can surely relate to an Asian heroine going on one.

My novel, Soulmated, is a young adult paranormal romance about empaths and psychics—it’s the farthest thing from being preachy—but maybe that’s not such a bad thing. After all, for most teens, genre fiction would rank quite a bit higher than their school’s required reading list. Part of me intuitively knew that setting my novel in a paranormal world might even attract someone who ordinarily wouldn’t have picked up a contemporary novel about an Indian-American girl because—let’s face it—some non-Indian-American readers might have looked at that book and thought they couldn’t relate.

My novel, Soulmated, is a young adult paranormal romance about empaths and psychics—it’s the farthest thing from being preachy—but maybe that’s not such a bad thing. After all, for most teens, genre fiction would rank quite a bit higher than their school’s required reading list. Part of me intuitively knew that setting my novel in a paranormal world might even attract someone who ordinarily wouldn’t have picked up a contemporary novel about an Indian-American girl because—let’s face it—some non-Indian-American readers might have looked at that book and thought they couldn’t relate.

That’s a learned response, because clearly, teen readers are connecting with hobbits, monsters, and vampires.

If a teen can relate to an elf going on a quest, they can surely relate to an Asian heroine going on one. (The Reader by Traci Chee or Silver Phoenix by Cindy Pon.) And how is a werewolf trying to save her pack any different than a Latinx bruja trying to save her family from a spell gone wrong? (Labyrinth Lost by Zoraida Córdova.) Even in my own novel, Laxshmi’s empath abilities are emerging, somewhat like superheroes who are just learning to use their powers. The only difference is that I’ve peppered references to my Indian-American culture, portraying her as any other girl struggling against pressures from home and expectations she balks at.

If a teen can relate to an elf going on a quest, they can surely relate to an Asian heroine going on one. (The Reader by Traci Chee or Silver Phoenix by Cindy Pon.) And how is a werewolf trying to save her pack any different than a Latinx bruja trying to save her family from a spell gone wrong? (Labyrinth Lost by Zoraida Córdova.) Even in my own novel, Laxshmi’s empath abilities are emerging, somewhat like superheroes who are just learning to use their powers. The only difference is that I’ve peppered references to my Indian-American culture, portraying her as any other girl struggling against pressures from home and expectations she balks at.

So why might teens find characters from marginalized groups, like mine or any others, difficult to relate to? Maybe it brings up uncomfortable issues they don’t want to face or don’t think affects them, like racism, bullying, and bigotry. Maybe their family has unknowingly taught them that our differences are more important than our similarities. Maybe they’ve learned that “other” is equivalent to “less than” and therefore not worth the effort. It all comes back to empathy and using compassion and understanding to connect with a fellow human being despite our outward differences.

According to the Melbourne Child Psychology Journal, the ability to empathize is a skill that is still developing during the teenage years and is on the rise beginning at about 13-15 years of age. It makes it even more important to provide stories from different perspectives to these teens. It’s like exercising the emerging skill. From my own experience with my 16-year-old son, reading, paired with the appropriate analysis and discussion, is definitely worth the effort. The only drawback, however, is that he quickly loses interest when he sees it as a lesson.

No one argues that a diet high in vegetables is healthy, but as every parent knows, sometimes smothering the broccoli with cheddar cheese is the best way to get it to go down. While comparing this to reading is a bit oversimplified, it does illustrate the idea that some “lessons” are more effective if we make them more palatable.

Laura M. Jiménez, PhD, in an interview with the blog Reading While White, describes her experience teaching diverse children’s literature to a group of mostly white women who were studying to become teachers. She said that they had a difficult time connecting with stories outside their lived experiences, but she also observed that the more stereotypical and trope-ful the book, the easier they were able to connect with it.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

If adults find diverse fiction easier to relate to when staged in commercial wrappings, it only reinforces an idea that we’ve already accepted: Sometimes it’s just easier to get a teen to enjoy reading if it’s genre fiction. And if it’s filled with characters written by #ownvoices authors? Even better.

Stories designated as #ownvoices provide an authentic view of what the “other” side looks like, and placing that fictional setting in a spaceship, a dystopian world, or one with psychics and empaths, might just be your handiest tool in creating a more empathetic reader.

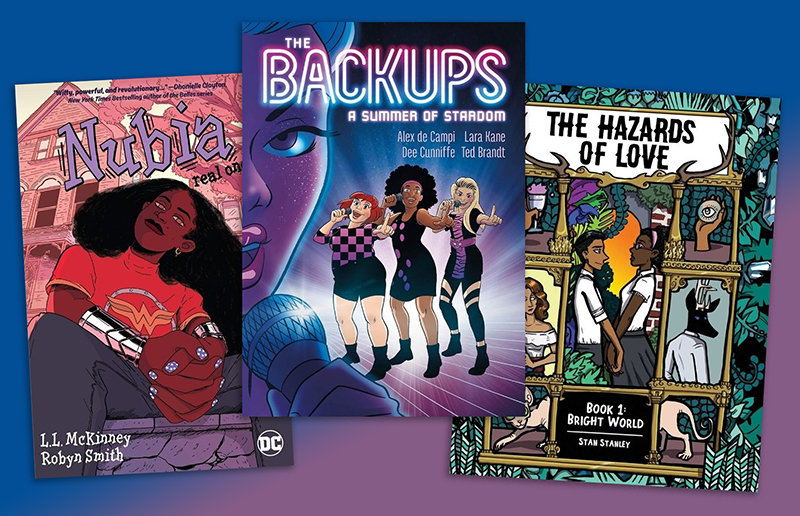

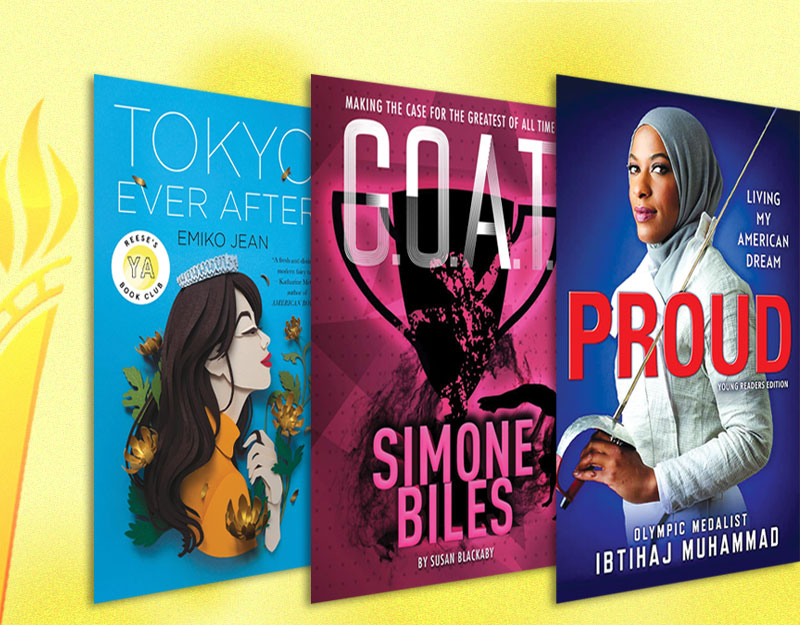

If you’re looking for ways to support more #ownvoices genre fiction, here are some suggestions:

- Have your readers write and post a book review of an #ownvoices work in their favorite subgenre and have them show similarities to a more established work with comparable tropes or themes.

- Start a book club for #ownvoices genre fiction, and don’t forget to tell the authors and publishers that you’ve chosen their books.

- Contact #ownvoices authors and ask them to speak via video conference call to a class or a book club. Most authors would love the opportunity.

A far wider selection of diverse books and resources now exists compared to even five years ago, but finding a curated list of #ownvoices genre fiction has been difficult. One of the most helpful sites for diverse young adult fiction (including both literary and commercial) is Diversity in YA. Another site that’s a great resource for multiple age groups is We Need Diverse Books. You can also search Tumblr and Goodreads lists for #ownvoices works. Although the lists are unlikely to be curated, it’s a great place to start and familiarize yourself with what’s out there and meet bloggers who are passionate about promoting #ownvoices speculative fiction.

BIO:

Shaila Patel is a pharmacist by training, a pediatric-office manager by day, and a writer by night. SOULMATED, her debut young adult paranormal romance won the 2015 Chanticleer Book Reviews Paranormal Awards in YA. A huge fan of epilogues, she also enjoys traveling, craft beer, tea, and reading in cozy window seats. She writes from her home in the Carolinas.

Shaila Patel is a pharmacist by training, a pediatric-office manager by day, and a writer by night. SOULMATED, her debut young adult paranormal romance won the 2015 Chanticleer Book Reviews Paranormal Awards in YA. A huge fan of epilogues, she also enjoys traveling, craft beer, tea, and reading in cozy window seats. She writes from her home in the Carolinas.

Contact Links:

Website (http://www.shailapatelauthor.com)

Facebook (http://bit.ly/2btIJLK)

Twitter (http://bit.ly/2aVbeiR)

Instagram (http://bit.ly/2btID6X)

Pinterest (http://bit.ly/2biBDeH)

Goodreads (http://bit.ly/2btJp3S)

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Heather Booth

Heather Booth has worked in libraries since 2001 and am the author of Serving Teens Through Reader’s Advisory (ALA Editions, 2007) and the editor of The Whole Library Handbook: Teen Servcies along with Karen Jensen.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

Who determines what is authentically Indian? Both you and conservative writer Dinesh D’Souza are Indian, but I would think that you would have more in common in your thinking with an Asian writer like Ellen Oh, and D’Souza would have more in common with African-American writer Thomas Sowell, than you and D’Souza would have with each other. And if you are both authentically Indian which is the case, how is that helpful to a young reader since your outlooks and your characters’ outlooks would be so different?

It’s helpful in illustrating that within any group there is a diversity of experiences and a diversity in career paths to take. The biggest reason why you’d be able to find commonalities between books by the authors you listed is because of the genre in which they write; speculative YA fiction doesn’t generally compete with political theory for space on the bookshelf.

Thank you for your comment and questions.

Authenticity in #ownvoices really refers to the authority of the author to tell his or her own story. You’re right in that Dinesh D’Souza and I would have vastly different experiences and therefore perspectives, but each no less authentic than the other. No culture, race, or religion is monolithic. If Dinesh D’Souza were to write an #ownvoices YA speculative fiction novel, his viewpoint would be just as enlightening to a young reader from outside our marginalized group as I would hope mine would be. His outlook would also be a fresh perspective to me.

No single #ownvoices novel could encapsulate or represent every experience in their community, and that’s why more #ownvoices authors are needed in YA literature. The fact that the outlooks from different authors from within a community would vary is precisely the point. In order for these books to teach empathy, teens need to read about authentic experiences different from their own–no matter how much the authors’ experiences vary. The more these teens read, we hope it’s easier for them to see that other perspectives exist and that they aren’t wrong just because they’re different.

I’m thrilled you responded, Shaila. You are right, in many ways.. if D’Souza were to write an #ownvoices YA novel, it would be his authentic voice. However, I bet a sensitivity reader and the SJWs would have a field day with it if D’Souza were to have the courage to create the same kind of depictions that were seen in Saroo Brierley’s A Long Way Home, D’Souza’s authenticity be darned. Weren’t the depictions of unsympathetic Indians unwilling to engage with a child who spoke Hindi instead of Bengali, human trafficking in children by Indians, and an adoption system in Indian that is willing to look outside of Indian culture harmful to a child who is Indian, or harmful to a person who is not Indian because it would give the wrong impression to impressionable. Does being #ownvoices does inoculate a writer from being accused of a harmful depiction of a culture with which the writer is intimately familiar? I don’t think so; look at the response to A Birthday Cake for George Washington.

Let’s just make a pact: if a book is #ownvoices, let the #ownvoice tell the story however the #ownvoice wants, as you did. You wrote wisely here, “No single #ownvoices novel could encapsulate or represent every experience in their community, and that’s why more #ownvoices authors are needed in YA literature.” Yes! Let’s drop this silly thing about harmful depictions if they come from #ownvoices, however the author defines that #ownvoice.

I’d just like to note here that the illustrator for A Birthday Cake for George Washington might have been Black, but the author wasn’t. That wasn’t an #ownvoices book and that is part of why there was a justifiable backlash against its errors. Also, #ownvoices means you are a person from that culture writing about your experience with that culture – so, again, A Birthday Cake would not fit.

The idea of #ownvoices is barely supportable for realistic fiction, considering that even people inside of a culture (say, an Indian like Shaila Patel) is really only #ownvoice for his or her tiny chunk of that culture (say, Goan, urban Sikh, Smarta Hindu, Oriya, Tamil, etc.). For an historical novel set anywhere before e.g. 1917, no one is #ownvoice because no one was alive in that period to experience it and be “of” it. For a science fiction or fantasy novel, same thing. No one is of that world really, even someone based on a person from the real world, so it’s an #ownvoice oxymoron.