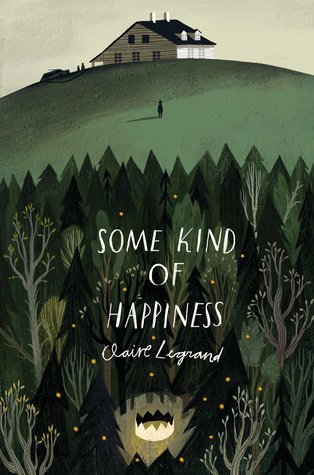

#MHYALit: It’s Okay Not to Be Okay, a guest post by author Claire Legrand

Some Kind of Happiness is one of those books that grabbed me from the first page and didn’t let go. I was a child with anxiety and Finley Hart is the first time I have ever seen an accurate representation of my mental state in childhood. We desperately need more middle grade stories that deal frankly with mental illness. Kids with anxiety and depression need to see themselves in stories so they can understand what they’re feeling and how to deal with it. Some Kind of Happiness is a special and important book, and it’s going to mean a lot to many, many kids and families. – Ally Watkins

In fifth grade, I had my first anxiety attack.

I don’t remember what prompted me to ask my teacher if I could use the restroom, but I remember huddling in the stall, hunched over on the toilet, as nausea seized my tiny ten-year-old body. My skin broke out in sick chills. I scratched my arms and legs until they were covered in red marks.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

My thoughts raced with fear; I could not quiet my brain. I tried going to the bathroom, I tried throwing up. Nothing helped. I simply sat there and endured it until I felt well enough to go back to class.

Part of me was terrified by what had just happened. But I rallied and got through the day, dismissing that scary moment in the bathroom as . . . something. I had no idea what to call it.

I decided I was fine. I was still breathing, still standing.

I was fine. (I wasn’t fine.)

In high school, I was busy. The depressive swings and anxiety attacks that had come and gone through middle school—that I had resolutely ignored—receded. Looking back, I honestly think my high school self sublimated my anxiety and depression into a ferocious, obsessive fixation on grades and achievement. If I couldn’t figure out my algebra homework, I sobbed and shook with panic, and stayed up late agonizing over my failure until I felt sick with exhaustion and self-loathing.

I remember sometimes pinching myself, hard—even slapping my own face—when I failed at a task. I remember feeling how completely my entire worth as a human being was tied up in achievement.

Because those things meant I was okay. That I was fine. That the sluggish middle school phase—those blue days, those spiraling thoughts—had passed. If I was an achiever, then I wasn’t sick or weird or broken.

I was fine. (I wasn’t.)

In college, depression hit me like a fist to the gut. The writing bug bit me and changed my life. I stopped studying music, leaving behind beloved friends and professors to forge a new path in life. I knew I wanted to write books, but beyond that I had no idea what the future held.

It became hard to get out of bed. I stopped taking care of myself. I stayed up all night, hardly slept, and even more rarely made it to class or work on time. I binged on salty, fatty foods one day and then barely ate the next. I got dressed in the dark and avoided mirrors so I wouldn’t have to look at my face or my body, both of which I despised.

Sometimes I would think about the effort required to get through another day and feel my whole self shrink and shrivel. I would retreat into my thoughts, curl up in a fetal position in bed, and not move for hours.

But I was fine. Honestly. (Or not.)

Despite the perpetual tardiness, I still got As in school. I wrote killer essays in my literature classes. I had an apartment, a job, friends. I figured out that I wanted to be a librarian. I got into graduate school.

There was nothing wrong with me. I thought: Doesn’t everyone have days when they can’t get out of bed because the thought of doing so makes their body clench up with fear? Doesn’t everyone low-level hate themselves pretty much all the time?

Sure, I thought. This is normal. This is fine.

(I was so far from fine.)

It took me years to put a name to what was wrong with me. It took me even longer to seek treatment—to see a therapist and finally, only a few months ago, start taking medication to help manage my mental health.

And it took me that long because I kept convincing myself that I was fine. Throughout everything—the panic attacks, the constant anxiety, the crushing depression—I wrote books, kept up with friends, started a serious romantic relationship. I worked out, cracked jokes, called my grandma on her birthday.

These are things, I thought, that normal people do. Therefore, I thought, I am normal.

(I am fine.)

It’s so easy, when someone asks you the question:

“How are you?” asks the sales clerk, the neighbor, the friend.

And you say, “I’m fine.” Society expects it of you. Nobody actually wants to hear what kind of messed-up emotional issues you’re struggling with (so we think). It’s not seemly to be seen on social media opening up about your depression, your anxiety, your self-loathing (so we are told).

And so you convince yourself you’re fine, even when you’re not: “I’m good! Busy, but can’t complain!” (I’ve been on the verge of tears all day.)

And so you craft lies: “My boyfriend’s car died, gotta go pick him up.” (I can’t get out of bed. The thought of doing so makes it hard to breathe.)

Because you can still function, after all. You can still smile and meet your deadlines, you still buy your groceries and make your bed (when you can get out of it). You’re not that sick. You’re not one of those people who really need help. I mean, sure, sometimes you let the dishes pile up because you feel so overwhelmed by literally every thought that runs through your head that all you can do to keep from totally losing it is curl up on the couch and try to hold yourself together.

But isn’t that how it is for everyone? (No. It’s not.)

Shouldn’t I be able to handle this without burdening others with the knowledge of my pain? (You don’t have to do that. You are not a burden to your friends. I promise you.)

In Some Kind of Happiness, Finley feels guilt and shame regarding her own anxiety and depression, which she has not yet named, or even fully acknowledged, because she doesn’t understand that it’s okay to reach out, to ask for help:

I have no right to my sadness when there are dead families and burned houses.

The memories of all the sadness I have ever experienced come rushing back to me in a stream. Days when I could nto smile, when I felt heavy and pushed down. nights when I could not sleep. Mornings when I could not wake up.

These moments of sadness seem so small, now. They seem pathetic.

That was me. I was Finley. I thought that since I was (mostly) fine, then I didn’t have to—and shouldn’t—speak up about what I was feeling. That it was best dealt with on my own. That people would scorn me if I opened up to them, tell me I had no real reason to complain.

That was me, for so long. But no longer.

Lately I’ve been trying more and more to be honest with my friends about what I’m feeling—and not just my safe, core group of friends who understand anxiety and depression because they experience it themselves.

All my friends. My family, too. When I’m not fine, I try to tell them, even when it feels scary or embarrassing. I don’t always find the courage, but I always at least think about it. And when I do open up to them, I don’t couch what I’m feeling in “safe” terms. I want to tell it like it is:

My throat and chest are tight with panic. I’ve barely moved from this chair all day.

I’m moving under the weight of an ocean today. It’s hard to think, hard to focus. My mind is fuzzy and dim.

My thoughts are spiraling faster and faster. They’re all I can hear.

I want them to understand what it feels like, as much as they can without experiencing it themselves. I want them to hear me describe how ugly anxiety and depression feel. I want them to experience discomfort when they hear me speak so frankly—and then I want them to push through that discomfort and come out the other side with a greater understanding of what I and so many other people around them experience on a daily basis.

Honesty paves the way for discussion, and discussion breeds empathy. The more people speak frankly about mental illness, the faster it will become part of the everyday conversation.

When more and more people candidly describe what it feels like to endure a depressive swing, to experience the quiet agony of constant anxiety, social taboos regarding mental health and mental illness crumble and fade.

When someone suffering in silence sees another human being opening up about their own struggles, they feel a little less alone and, maybe, a little more hopeful.

I won’t always talk about my mental health on social media. It’s important to keep certain things between myself, my family, and my close friends.

But sometimes things need to be said and discussions need to happen. Sometimes standing up to speak is the most important thing you can do to make a difference in others’ lives, and I am going to try my best to do that—for myself, and for my readers, especially my kid and teen readers who, like Finley, may not yet understand what they’re feeling. And maybe if they see me speaking frankly about mental illness as part of my everyday experience—right alongside my tweets about unicorns and Tumblr gifs from my favorite TV shows—they’ll find the courage to do the same.

Because sometimes all a person in pain needs to hear is this:

I’m not fine. Not always. I’m afraid to say it, but I’m going to say it anyway: I’m not fine, and it’s okay to say so.

(And it’s okay for you to say so, too.)

About SOME KIND OF HAPPINESS by Claire Legrand

THINGS FINLEY HART DOESN’T WANT TO TALK ABOUT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

• Her parents, who are having problems. (But they pretend like they’re not.)

• Being sent to her grandparents’ house for the summer.

• Never having met said grandparents.

• Her blue days—when life feels overwhelming, and it’s hard to keep her head up. (This happens a lot.)

Finley’s only retreat is the Everwood, a forest kingdom that exists in the pages of her notebook. Until she discovers the endless woods behind her grandparents’ house and realizes the Everwood is real–and holds more mysteries than she’d ever imagined, including a family of pirates that she isn’t allowed to talk to, trees covered in ash, and a strange old wizard living in a house made of bones.

With the help of her cousins, Finley sets out on a mission to save the dying Everwood and uncover its secrets. But as the mysteries pile up and the frightening sadness inside her grows, Finley realizes that if she wants to save the Everwood, she’ll first have to save herself.

Reality and fantasy collide in this powerful, heartfelt novel about family, depression, and the power of imagination. (Simon and Schuster, May 17, 2016)

Meet Claire Legrand

Claire Legrand is the author of books for children and teens, including The Cavendish Home for Boys and Girls, The Year of Shadows, Winterspell, Some Kind of Happiness, and Foxheart. She is also one of the four authors of The Cabinet of Curiosities. When not writing books, she can be found obsessing over DVD commentaries, going on long walks (or trying to go on long runs), and speaking with a poor English accent to random passersby. She thinks musicians and librarians are the loveliest of folks (having been each of those herself) and, while she loves living in central New Jersey, she dearly misses her big, brash, beautiful home state of Texas.

Filed under: #MHYALit, Uncategorized

About Karen Jensen, MLS

Karen Jensen has been a Teen Services Librarian for almost 30 years. She created TLT in 2011 and is the co-editor of The Whole Library Handbook: Teen Services with Heather Booth (ALA Editions, 2014).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

Claire,

Wow. You are brave and I’m happy you write this book. My crippling anxiety started at age 8, and has continued to this day. And I’m a writer – and could so relate to all you shared. I’m managing mine – and mostly days are good. Keep the faith and keep being honest.

Warm wishes

Elle