#MHYALit: Teens, Mental Health and the Places it Takes Them, a guest post by Kerry Sutherland

Today Kerry Sutherland discusses some recent titles she has read that depict teens in marginalized situations as a result of mental health in their lives.

See all of the posts in our Mental Health in Young Adult Literature series here.

Many of the books I have discovered during my time with the In the Margins book selection and award committee (whether they were or are ultimately chosen for our list or not), involve teens not only in marginalized situations (foster care, prison, homelessness, poverty, or a cycle of any or all of these conditions) but teens who find themselves in those situations because of mental illness. Many teens struggle with mental illness themselves or are affected by the illness of a family member or friend, but when that illness creates havoc with their daily lives by forcing them into homelessness, foster care, or dangerous situations, that illness takes on an authority and control that makes them even more vulnerable, limiting their chances of recovery and a healthy life.

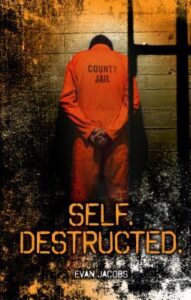

In Evan Jacobs’s Self.Destructed, a relatively short, larger print Gravel Road (Saddleback) publication that would appeal to teens with reading challenges, we meet Michael, who comes from a working class family where his father puts in overtime to provide and has little time for his children. Michael runs for the track team and has dreams of becoming a pediatrician, but his social awkwardness concerns him. He knows he has difficulty understanding social situations and handling conversations, but when he meets beautiful new student Ashley, he feels as if he can talk to her without fearing judgment. Ashley likes running, too, and she finds him interesting because he’s “different.” Rich and popular, Ashley seems tired of the in-crowd, and as she and Michael spend more time together, he feels as if he has broken some barrier within himself, where he “pushed people away because he couldn’t let things go.” The pressure he feels from his parents to succeed in school, do well on the SAT, and go to college fades in the background when he’s with Ashley, and he becomes defensive about their relationship when his friends tease him. His very literal and concrete thinking get in the way, however, when he criticizes Ashley for having a Justin Bieber song on her iPod, because he believes that the music is “fake,” and he thought that Ashley wasn’t. She tries to explain that to her, the song is just something fun to listen to, but he overreacts, and she (understandably) begins to avoid him. His obsession with her grows worse when he discovers she is dating a football player who is rich and popular like she is, and he begins to stalk her. His father tells him to stop being a baby and get over her, but Michael decides he’s rather be dead than have to see her at school every day. He feels as if “everyone’s against me now” and thinks that if he brought a gun from his father’s locked gun case to school, Ashley might be impressed. When he pulls the gun on Ashley and her friend, however, he is arrested and taken to jail, in spite of his protests that he hadn’t planned to hurt anyone. He is sentenced to a detention facility, where he keeps to himself to stay out of trouble, focusing on schoolwork and continuing to obsess over what he views as the unfairness of the situation. “All I wanted was to be close to Ashley,” he insists, and wonders how he can be “a criminal” and “a bad guy . . . but I’m not.” The barriers in his thought process, aversion to loud people, and social awkwardness all point to the possibility of an undiagnosed autism spectrum disorder, which makes his obsessive tendencies more difficult to manage. As long as he continues to blame others for his incarceration, he can’t move forward, and his obsession with Ashley and when he will get to see her continues after his release into his grandmother’s care, where he is required to stay and attend an alternative school until he is 18. He makes more mistakes in service of his obsession, including stealing his cousin’s car and crashing his former school’s prom to see Ashley, before he admits that when he brought the gun to school he intended to kill himself in front of her. He begins to understand that he has been his own worst enemy, focusing on the past instead of the future, and is determined to work through whatever life throws at him, accepting the assistance of his alternative school’s principal and some new friends. His paranoid and self destructive thoughts will still be an issue, but he accepts them for what they are instead of refusing to acknowledge them, and in facing them, can begin to think positively about what the future holds.

In Evan Jacobs’s Self.Destructed, a relatively short, larger print Gravel Road (Saddleback) publication that would appeal to teens with reading challenges, we meet Michael, who comes from a working class family where his father puts in overtime to provide and has little time for his children. Michael runs for the track team and has dreams of becoming a pediatrician, but his social awkwardness concerns him. He knows he has difficulty understanding social situations and handling conversations, but when he meets beautiful new student Ashley, he feels as if he can talk to her without fearing judgment. Ashley likes running, too, and she finds him interesting because he’s “different.” Rich and popular, Ashley seems tired of the in-crowd, and as she and Michael spend more time together, he feels as if he has broken some barrier within himself, where he “pushed people away because he couldn’t let things go.” The pressure he feels from his parents to succeed in school, do well on the SAT, and go to college fades in the background when he’s with Ashley, and he becomes defensive about their relationship when his friends tease him. His very literal and concrete thinking get in the way, however, when he criticizes Ashley for having a Justin Bieber song on her iPod, because he believes that the music is “fake,” and he thought that Ashley wasn’t. She tries to explain that to her, the song is just something fun to listen to, but he overreacts, and she (understandably) begins to avoid him. His obsession with her grows worse when he discovers she is dating a football player who is rich and popular like she is, and he begins to stalk her. His father tells him to stop being a baby and get over her, but Michael decides he’s rather be dead than have to see her at school every day. He feels as if “everyone’s against me now” and thinks that if he brought a gun from his father’s locked gun case to school, Ashley might be impressed. When he pulls the gun on Ashley and her friend, however, he is arrested and taken to jail, in spite of his protests that he hadn’t planned to hurt anyone. He is sentenced to a detention facility, where he keeps to himself to stay out of trouble, focusing on schoolwork and continuing to obsess over what he views as the unfairness of the situation. “All I wanted was to be close to Ashley,” he insists, and wonders how he can be “a criminal” and “a bad guy . . . but I’m not.” The barriers in his thought process, aversion to loud people, and social awkwardness all point to the possibility of an undiagnosed autism spectrum disorder, which makes his obsessive tendencies more difficult to manage. As long as he continues to blame others for his incarceration, he can’t move forward, and his obsession with Ashley and when he will get to see her continues after his release into his grandmother’s care, where he is required to stay and attend an alternative school until he is 18. He makes more mistakes in service of his obsession, including stealing his cousin’s car and crashing his former school’s prom to see Ashley, before he admits that when he brought the gun to school he intended to kill himself in front of her. He begins to understand that he has been his own worst enemy, focusing on the past instead of the future, and is determined to work through whatever life throws at him, accepting the assistance of his alternative school’s principal and some new friends. His paranoid and self destructive thoughts will still be an issue, but he accepts them for what they are instead of refusing to acknowledge them, and in facing them, can begin to think positively about what the future holds.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Ruby, the title character in P.D. Workman’s drama-packed novel, has just about every problem imaginable, but claims that she is just fine. She loves the freedom she has in foster care, as she bounces around between homes, ignores rules, hooks up with whichever boy feels right at the time, and cuts school as she pleases. Nothing is important to her except her sister Ronnie, who has ended up in foster care as well, but she isn’t supposed to be in contact with her because they were both victims of their father’s sexual abuse, a fact that Ruby refuses to admit. Ruby drowns her memories and feelings with alcohol and drugs, along with the physical attention of boys and disturbingly, her adult male social worker, who reveals that he has been having sex with her since she was nine. “It was Ruby’s idea,” he insists, “and she kept it going” as if a nine year old, who is eleven when the social worker is busted for his crime, is to blame for his actions, because she is “manipulative” and “a flirt.” Ruby doesn’t think he did anything wrong, either, since she enjoyed the comfort he offered, and thinks it is all a big deal about nothing. As she seeks out more of the same, the inevitable happens and she gets pregnant at age 13. Not surprisingly, she denies her condition until she actually goes into labor, and afterwards refers to her baby as “it” and leaves her care to friends. The world feels “too complex” to her, but still, she doesn’t think she has a problem, and if anything had happened to her at home with her father, “wouldn’t I remember?” Foster parents abuse her, her social worker takes advantage of her, and ultimately, her acceptance of this mistreatment comes from her parents’ behavior, as it is revealed that her father would get her drunk and have sex with her, followed by her mother’s assistance in removing any evidence by bathing her immediately afterwards. When anything bad happens now, she just tries to forget about it, but the manner in which she does is clearly self-destructive. As the story continues, her reactions to situations reveal that she clearly has Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and depression, along with a reading disability and issues with empathy, and her efforts to cope with all of this result in another pregnancy, gang-related violence (including witnessing murder, although she considers the gang “protection”), drug rehab, and a stroke at the age of 15. While the ending offers Ruby some hope in the form of a police officer who falls in love with her and wants to help her overcome her past, Ruby’s struggle has deprived her of a normal childhood and adolescence that will make a healthy adult experience seem nearly impossible. While the abuse is the cause of her PTSD and other mental health factors, it is her refusal to accept that she needs help and the failure of adults who should be protecting her to follow up on treatment that keeps her on the streets, as her search for attention and validation puts her in constant danger.

Ruby, the title character in P.D. Workman’s drama-packed novel, has just about every problem imaginable, but claims that she is just fine. She loves the freedom she has in foster care, as she bounces around between homes, ignores rules, hooks up with whichever boy feels right at the time, and cuts school as she pleases. Nothing is important to her except her sister Ronnie, who has ended up in foster care as well, but she isn’t supposed to be in contact with her because they were both victims of their father’s sexual abuse, a fact that Ruby refuses to admit. Ruby drowns her memories and feelings with alcohol and drugs, along with the physical attention of boys and disturbingly, her adult male social worker, who reveals that he has been having sex with her since she was nine. “It was Ruby’s idea,” he insists, “and she kept it going” as if a nine year old, who is eleven when the social worker is busted for his crime, is to blame for his actions, because she is “manipulative” and “a flirt.” Ruby doesn’t think he did anything wrong, either, since she enjoyed the comfort he offered, and thinks it is all a big deal about nothing. As she seeks out more of the same, the inevitable happens and she gets pregnant at age 13. Not surprisingly, she denies her condition until she actually goes into labor, and afterwards refers to her baby as “it” and leaves her care to friends. The world feels “too complex” to her, but still, she doesn’t think she has a problem, and if anything had happened to her at home with her father, “wouldn’t I remember?” Foster parents abuse her, her social worker takes advantage of her, and ultimately, her acceptance of this mistreatment comes from her parents’ behavior, as it is revealed that her father would get her drunk and have sex with her, followed by her mother’s assistance in removing any evidence by bathing her immediately afterwards. When anything bad happens now, she just tries to forget about it, but the manner in which she does is clearly self-destructive. As the story continues, her reactions to situations reveal that she clearly has Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and depression, along with a reading disability and issues with empathy, and her efforts to cope with all of this result in another pregnancy, gang-related violence (including witnessing murder, although she considers the gang “protection”), drug rehab, and a stroke at the age of 15. While the ending offers Ruby some hope in the form of a police officer who falls in love with her and wants to help her overcome her past, Ruby’s struggle has deprived her of a normal childhood and adolescence that will make a healthy adult experience seem nearly impossible. While the abuse is the cause of her PTSD and other mental health factors, it is her refusal to accept that she needs help and the failure of adults who should be protecting her to follow up on treatment that keeps her on the streets, as her search for attention and validation puts her in constant danger.

Sixteen year old Arlie in Mandy Mikulencak’s Burn Girl has been a parent to her drug-addicted mother for as long as she can remember, but she is certain that her stepfather Lloyd is to blame for her mother’s problem. Lloyd is also responsible for the meth lab explosion that burned Arlie’s face six years before, landing her in the hospital and burn rehab, then foster care before her mother found her and the two of them ran away in fear of Lloyd. Arlie’s home has been a filthy motel room frequented by her mother’s druggie ‘friends,’ and while she tries to keep the room relatively clean for herself and her mother, she is haunted by her mother’s instructions that Arlie do the ultimate cleaning if and when her mother ODs: flush any drugs and make sure her mother is wearing clean panties. Arlie has tried to be invisible, both because she and her mother are in hiding but also because of her facial scar, which earns her the name “fire freak” at school, but when the worst happens and her mother is dead, the authorities pay attention. Her mother’s brother, unknown to Arlie until now, steps up to take custody, and the two of them make an attempt at a relationship. He reveals that her mother’s addiction began long before she met Lloyd, and Arlie admits that her mother’s mental illness has made her childhood a lonely and defensive one: “Mom had a way of making me feel lonely even when she was right by my side.” She tells her uncle that she is willing to try to make things work with him, but she “doesn’t need rescuing.” Her efforts to move forward lead to focusing on the school choir and a romance with a blind boy who truly cares for her regardless of her past help her deal with mean girls and stumbling blocks in her relationship with her uncle, but nothing prepares her for the very real threat her murderous, drug-dealing stepfather poses when he shows up in town. Arlie, whose childhood has been stolen through her mother’s addiction, has the support she needs to deal with her feelings about her mother and their past, which has included foster care, homelessness, and poverty. Without that support, she may have followed her mother’s footsteps to manage the intensity of those emotions, like Ruby.

Sixteen year old Arlie in Mandy Mikulencak’s Burn Girl has been a parent to her drug-addicted mother for as long as she can remember, but she is certain that her stepfather Lloyd is to blame for her mother’s problem. Lloyd is also responsible for the meth lab explosion that burned Arlie’s face six years before, landing her in the hospital and burn rehab, then foster care before her mother found her and the two of them ran away in fear of Lloyd. Arlie’s home has been a filthy motel room frequented by her mother’s druggie ‘friends,’ and while she tries to keep the room relatively clean for herself and her mother, she is haunted by her mother’s instructions that Arlie do the ultimate cleaning if and when her mother ODs: flush any drugs and make sure her mother is wearing clean panties. Arlie has tried to be invisible, both because she and her mother are in hiding but also because of her facial scar, which earns her the name “fire freak” at school, but when the worst happens and her mother is dead, the authorities pay attention. Her mother’s brother, unknown to Arlie until now, steps up to take custody, and the two of them make an attempt at a relationship. He reveals that her mother’s addiction began long before she met Lloyd, and Arlie admits that her mother’s mental illness has made her childhood a lonely and defensive one: “Mom had a way of making me feel lonely even when she was right by my side.” She tells her uncle that she is willing to try to make things work with him, but she “doesn’t need rescuing.” Her efforts to move forward lead to focusing on the school choir and a romance with a blind boy who truly cares for her regardless of her past help her deal with mean girls and stumbling blocks in her relationship with her uncle, but nothing prepares her for the very real threat her murderous, drug-dealing stepfather poses when he shows up in town. Arlie, whose childhood has been stolen through her mother’s addiction, has the support she needs to deal with her feelings about her mother and their past, which has included foster care, homelessness, and poverty. Without that support, she may have followed her mother’s footsteps to manage the intensity of those emotions, like Ruby.

Alice and Celia of Emiko Jean’s We’ll Never Be Apart is a particularly disturbing tale of twins at the mercy of the foster care system from a young age who spin out of control quickly, resulting in severe mental health problems that lead to arson and murder. When the story begins, Alice is in a mental health hospital, trying to deal with the fact that Celia set a fire that killed Alice’s boyfriend, Jason, who the two girls met in foster care and have been close to for years. Alice knows that Celia is in the same facility and is determined to find her and kill her, believing that she will never have a chance at happiness with Celia by her side. Alice begins to keep a journal and reveals the details of their childhood, which began to fall apart with the death of their grandfather, with whom they lived. The grandfather died on their sixth birthday, and they ate the cake as it grew stale over several days before a neighbor discovered the grandfather’s body, so Alice has violent flashbacks whenever she is offered cake. Alice and Celia’s troubles began with dangerous behaviors in foster care, including setting fires, which brings Celia a measure of peace. Alice knows she “will be better off without her” and blames Celia for the horror their lives have become, as Celia’s madness has only hurt Alice. The medical charts are “marked with an asterisk. A tiny star that said without words or writing that there was a darkness inside of us” Alice notes, and her battle with her twin, who is jealous of her romance with Jason, she believes, will be to the death. She pretends to take her meds, and without them, memories come flooding back, memories of abusive foster parents, a string of social workers, devastating fires, alcohol abuse, and ultimately, the revelation that Celia is not Alice’s twin, but a second personality, a “dark partner” or “twisted twin” Alice developed to absorb the negative feelings and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder that came with the death of her grandfather and the experiences that followed. The “terrible love” Celia has for Alice is a way for Alice to protect herself from further pain, but leaves her institutionalized, first in foster care and then in a mental health facility. It is only after Alice accepts Celia for what she is and takes responsibility for her actions can she move forward towards a better life.

Alice and Celia of Emiko Jean’s We’ll Never Be Apart is a particularly disturbing tale of twins at the mercy of the foster care system from a young age who spin out of control quickly, resulting in severe mental health problems that lead to arson and murder. When the story begins, Alice is in a mental health hospital, trying to deal with the fact that Celia set a fire that killed Alice’s boyfriend, Jason, who the two girls met in foster care and have been close to for years. Alice knows that Celia is in the same facility and is determined to find her and kill her, believing that she will never have a chance at happiness with Celia by her side. Alice begins to keep a journal and reveals the details of their childhood, which began to fall apart with the death of their grandfather, with whom they lived. The grandfather died on their sixth birthday, and they ate the cake as it grew stale over several days before a neighbor discovered the grandfather’s body, so Alice has violent flashbacks whenever she is offered cake. Alice and Celia’s troubles began with dangerous behaviors in foster care, including setting fires, which brings Celia a measure of peace. Alice knows she “will be better off without her” and blames Celia for the horror their lives have become, as Celia’s madness has only hurt Alice. The medical charts are “marked with an asterisk. A tiny star that said without words or writing that there was a darkness inside of us” Alice notes, and her battle with her twin, who is jealous of her romance with Jason, she believes, will be to the death. She pretends to take her meds, and without them, memories come flooding back, memories of abusive foster parents, a string of social workers, devastating fires, alcohol abuse, and ultimately, the revelation that Celia is not Alice’s twin, but a second personality, a “dark partner” or “twisted twin” Alice developed to absorb the negative feelings and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder that came with the death of her grandfather and the experiences that followed. The “terrible love” Celia has for Alice is a way for Alice to protect herself from further pain, but leaves her institutionalized, first in foster care and then in a mental health facility. It is only after Alice accepts Celia for what she is and takes responsibility for her actions can she move forward towards a better life.

Michael, Ruby, Arlie, and Alice, teens with lives in chaos because of the mental illness that has taken control over their lives, are well-crafted characters that teen readers will be able to relate to, either as those with shared experiences and feelings or as readers interested in the difficulties other teens face. These characters and their stories would be helpful for adults working with teens to help understand behaviors that otherwise seem needlessly self-destructive and isolating, because teens dealing with marginalized situations because of mental illness may seem interested in becoming invisible, like Arlie, or hurting others and themselves, like Michael, Ruby, and Alice, when in reality, they need understanding, patience, and above all, a friend to trust when their experience with the world is anything but hopeful.

Meet Our Guest Blogger, Kerry Sutherland

I am the teen librarian at the Ellet Branch of the Akron-Summit County Public Library in Akron, Ohio, and have a PhD in American literature from Kent State University, along with a MLIS from the same. I am a book reviewer for School Library Journal and RT Book Reviews magazine, as well as a published author of fiction, poetry, professional and academic work. I love cats, Henry James, NASCAR, and anime. I read everything, because you only live once.

Filed under: #MHYALit

About Karen Jensen, MLS

Karen Jensen has been a Teen Services Librarian for almost 30 years. She created TLT in 2011 and is the co-editor of The Whole Library Handbook: Teen Services with Heather Booth (ALA Editions, 2014).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#211)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: Dusti Bowling’s Latest – The Beat I Drum (Apr 2025)

Kevin McCloskey on ‘Lefty’ | Review and Drawn Response

Notable NON-Newbery Winners: Waiting for Gold?

The Seven Bills That Will Safeguard the Future of School Librarianship

Gayle Forman Visits The Yarn!

ADVERTISEMENT