#MHYALit post: On depression and Melina Marchetta’s Saving Francesca, by author Carrie Mesrobian

Today as part of the #MHYALit Discussion author Carrie Mesrobian discusses Saving Francesca by Melina Marchetta. SEE ALL OF THE #MHYALIT POSTS HERE

It should be stated up front that I’m not rational when it comes to Melina Marchetta. I love her novels so much that I’ve purposefully not read a few of them – I don’t want to live in a world where there’s no more Melina Marchetta to consume.

It should be stated up front that I’m not rational when it comes to Melina Marchetta. I love her novels so much that I’ve purposefully not read a few of them – I don’t want to live in a world where there’s no more Melina Marchetta to consume.

Loving an author so much you won’t read all her books? Like I said: not rational.

So, re-reading Marchetta’s Saving Francesca for the purpose of the Mental Health in YA Literature Project was a delight. And re-reading it with an eye toward the issues of depression and mental health was particularly illuminating.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

(Below will feature some minor details of the story which could be construed as “spoilers” depending on how much of a purist you are about that kind of thing. Take caution as you deem necessary.)

If you’re unfamiliar with the story, it’s about a girl whose mother one day does not get out of bed. She doesn’t go to work, or dress or eat, or even talk or behave with the same vigor and personality as before. Francesca’s mother Mia is generally a vibrant, hard-charging woman with a job at a university and the driving force of the Spinelli family. So what happens when she “disappears” through depression from her husband and children, sequestered and inert in her bedroom, is what makes up the bulk of the story.

Francesca is already not having a banner year when the story opens. She’s switched to a new school, an all-boys establishment that has only recently allowed female students, and finding a core of friends is almost as difficult as finding her own sense of self.

Despite all this, Saving Francesca has a lot of funny parts in it, which is often the case with dark and grim topics. But it’s also a refreshing take on how depression can affect an entire family system. Francesca’s little brother Luca doesn’t know what to call the situation; her father Robert is pretending everything’s fine while not understanding how to wash school uniforms or buy groceries for meals. Francesca watches her mother vomit in the sink and wants desperately to say something helpful:

But I stand and I stare. She senses me there and looks for a moment. I don’t know what she reads from my face. Am I angry? Sickened? Ashamed?

I want to say, Please, Mummy, be okay, please be okay, because if you’re not okay, we’ll never be.

But I say nothing.

I just go to school. (p. 107)

The relatives step in, trying to give support, but also alienating everyone as each kid must go live with separate grandmothers. One grandmother wants to take Francesca’s mother to her personal doctor; Robert refuses to allow this. Other well-meaning friends blame Robert for “causing” the depression by not being a good enough spouse. Nobody knows what to call the mysterious “thing” that has happened to Mia Spinelli. Young Luca is trying hard to piece it together, using words he’s overheard from other adults:

“Mummy’s having a nervous breakdown,” he says, and I can tell he has no idea what it is. (p. 57)

Mia’s niece Angelina takes Francesca to coffee and is more specific:

“It’s depression, Frankie.”

“I don’t understand. Sad people with sad lives are depressed. Mia’s not one of them.”

Angelina takes hold of my hand.

“I think everything’s just shut down on her. Maybe for one reason or maybe for a thousand. It’s kind of like a grief, and it’s not a puzzle that you’re supposed to work out on your own, Frankie. But I’ll tell you this. Mia is not going to get better being looked after by her mother. You have to find a way of getting back home. For you and Robert and Luca and Mia to get back together—and then you start from there.” (pp. 90-91.)

Here is the problem with well-meaning advice: it’s always only partially right. While Angelina is correct to call depression what it is –not sadness but more of an absence than any kind of specific feeling—she’s wrong to set up Francesca as being able to alleviate her mother’s problem. In fact, much of the book is involved with various members of the Spinelli family wondering how they caused Mia’s depression, how they are culpable for it, and therefore, must make amends to fix the problem.

Certainly, we can all make changes in our own behavior and expectations, but when it comes to depression, the locus of control resides mainly within the depressed person. It’s a terrifying situation, as the people who love the depressed person feel so helpless and are scrambling for solutions. But truly, the person who can’t seem to get out of bed or make any kind of change is the one that must make a move. That is the horrible reality of depression.

Whether that move is visiting a doctor or therapist, taking medications, entering a hospital, or making changes in work and home life doesn’t really matter. Any kind of move away from depressive thinking – what is often called “opposite action” in Dialectal Behavior Therapy practice—is called for and is incumbent on the depressed person.

But that doesn’t mean the family surrounding the depressed person feels fine. Established boundaries and structures are obliterated when depression invades a family. There’s a loss but it’s not one that Hallmark makes a sympathy card for. Depression has transformed a person they love and know well into a stranger and a ghost. How do you explain that to people in an easy-to-understand way? And what is the solution to living with a ghost?

One of the solutions in Saving Francesca is the use of medication in treating depression. Francesca’s friend Tom Mackee speaks somewhat vaguely and darkly about his experience with this:

“Antidepressants,” Thomas suggests. “My father was on them for six months once. Fun times.” (p. 155)

But Francesca’s father dismisses the problem:

“Do you think I haven’t looked into this?” he asks. “She doesn’t have a chemical imbalance. She doesn’t need to get addicted to something. She doesn’t need tablets giving her nightmares.” (p. 156)

Robert is referring to the medications given to his wife’s mother for her own bout of depression decades earlier, which at the time included tranquilizers or stimulants that were addictive of impairing on their own. Francesca is entering into a medical debate about a mood disorder for which there is a long-standing stigma and lack of clarity. In this case, Mia has had a miscarriage and what Robert is advocating for is that his wife’s depression is situational, the result of unexpressed grief from the miscarriage as well as the recent loss of Mia’s own father. This very well could be the case; many people have taken medications for situation depression, while others have taken nothing for major depression. It varies wildly, but at this point in time, medication has been established as a viable tool for combating either type, so it makes sense that it’s mentioned.

Alongside the giant hole that Mia’s depression creates, Francesca is trying to survive a new high school, breakdowns in friendship groups, and a devastating crush on a boy she can’t understand. She’s living your basic adolescent life while coping with a parent with a serious illness. Saving Francesca isn’t about fixing depression as much as it is learning to live amidst it. Since Francesca isn’t a doctor or a counselor, she must find other mechanisms for living through ambiguity and loss. Some of these include

- dancing like a total joyful idiot in drama class

- asking for respite and naps in the sofa of an empathetic teacher’s office

- admitting to her new friends what is happening

- researching “depression” on the internet

- making phonecalls to her mother’s friends and colleagues where she tries to explain the situation and gain support

- arguing with her father

- going to parties, drinking too much and dancing to terrible music

- checking in with her brother during the school day

- speaking the whole truth from her mind, even though it’s scary (and sometimes earns her detention)

Looking at this list of remedies, it makes sense that the solution for depression might be as complex as the naming of it. It’s an array of coping mechanisms. Francesca saving herself is truly the project of the book, and for those of us with experience with mental illness, also the difficult task for those affected. How you save yourself will look different for everyone. It’s not a linear, rational process. Depression can be chronic; for some it’s never truly defeated. One of the best parts of the book is the acknowledgment of that fact; Mia’s not fixed by the end of the book and the family never “goes back to normal.” Everyone is changed by depression entering their lives.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

But I believe the part of Francesca that speaks the whole truth is what actually saves her. This is one of the big reasons I think this book is so good. I highly recommend it for people interested in family dynamics and depression (it doesn’t hurt that I also think that for whatever bewitching reason, Australian YA writers are just so consistently on point when it comes to fiction. Why is that? Is it the water? The proximity to the South Pole? I welcome your theories).

If you like the book, please also check out The Piper’s Son, which is a companion novel from the point-of-view her Francesca’s friend Tom, featuring many of the characters introduced in Saving Francesca. I even got a tattoo in homage to it, in fact. Read both and then tell me what you think.

(Maybe I’ll tell you the tattoo story, too…)

But don’t tell me what happens in Looking For Alibrandi. I’m saving it to read for some later celebratory date.

Meet Author Carrie Mesrobian:

Carrie Mesrobian is the author of Sex & Violence, Perfectly Good White Boy and Cut Both Ways. Her next book, Just A Girl, comes out in 2017.

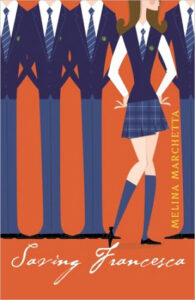

About SAVING FRANCESCA by Melina Marchetta:

A compelling story of romance, family, and friendship with humor and heart, perfect for fans of Stephanie Perkins and Lauren Myracle.

Francesca is stuck at St. Sebastian’s, a boys’ school that pretends it’s coed by giving the girls their own bathroom. Her only female companions are an ultra-feminist, a rumored slut, and an impossibly dorky accordion player. The boys are no better, from Thomas, who specializes in musical burping, to Will, the perpetually frowning, smug moron that Francesca can’t seem to stop thinking about.

Then there’s Francesca’s mother, who always thinks she knows what’s best for Francesca—until she is suddenly stricken with acute depression, leaving Francesca lost, alone, and without an inkling of who she really is. Simultaneously humorous, poignant, and impossible to put down, this is the story of a girl who must summon the strength to save her family, her social life and—hardest of all—herself.

Knopf, 2006

Filed under: #MHYALit

About Karen Jensen, MLS

Karen Jensen has been a Teen Services Librarian for almost 30 years. She created TLT in 2011 and is the co-editor of The Whole Library Handbook: Teen Services with Heather Booth (ALA Editions, 2014).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

More Geronimo Stilton Graphic Novels Coming from Papercutz | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT