#MHYALit: You Are Not Alone, The Primary Message by E. Sparling

Today’s post about working with teens in the library and the subject of mental health is a pseudonymous post in order to protect the identity of the teen in question. The author has tried to remove any identifiable characteristics while reminding us by sharing a real life example of how important the work that we do can be in the life of our teen patrons.

It was sort of a beeline, or a stride, but whatever you might label it as, a student was walking towards my circulation desk with a purpose.

“Hi. How are you? Do you have any books on being in a psychiatric hospital? I was in one over the weekend and it was terrible.”

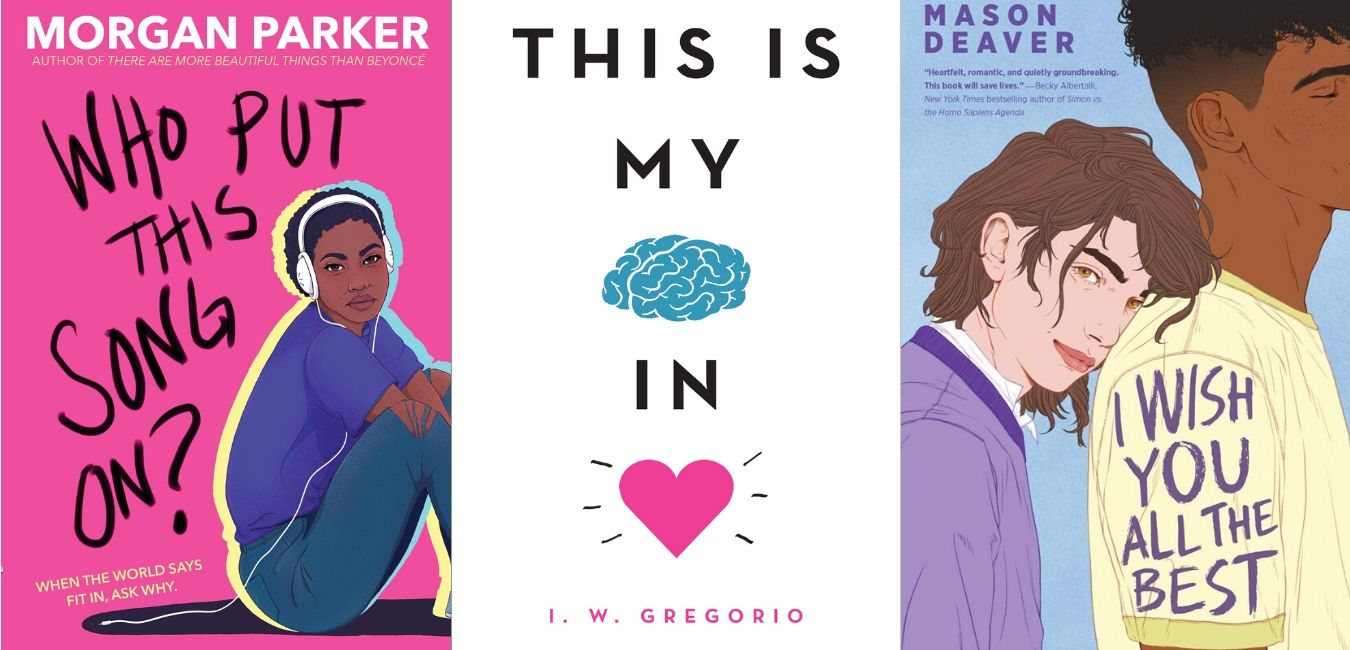

As I struggled to find words to help him, I clicked unconsciously on our catalog and performed what I thought were several quality searches. I returned only non-fiction volumes on mental illnesses with soft focus 80s covers and information that was dry at best and outdated at worst. I knew from my past five years as a teen librarian that there was fiction out there–Belzhar by Meg Wolitzer, It’s Kind of a Funny Story by Ned Vizzini (whose own demons had tragically won out). Yet I knew that at that precise moment fiction wasn’t exactly what he was looking for. Maybe at some point it would be a balm, but for now he needed to know that real people had gone through what we was going through, what he had witnessed in his harried weekend at an in-patient facility. He divulged no more details about why he had landed there, nor did I ask for them, figuring that they would be revealed in his own time, if at all. Yet his horror at what he had seen there rang true–I’d had a close family member spend time in a psychiatric facility and my own SAD lamp sat in plain sight on my circulation desk. I contacted that family member on the same day, knowing that her unique perspective could help more than mine could.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

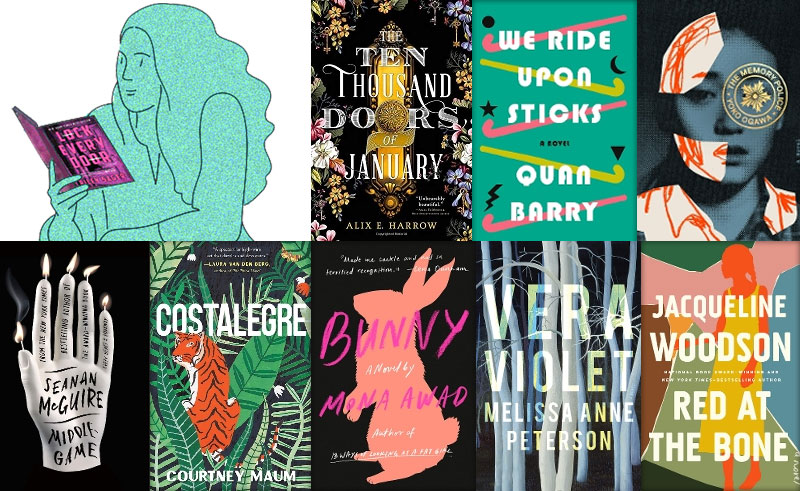

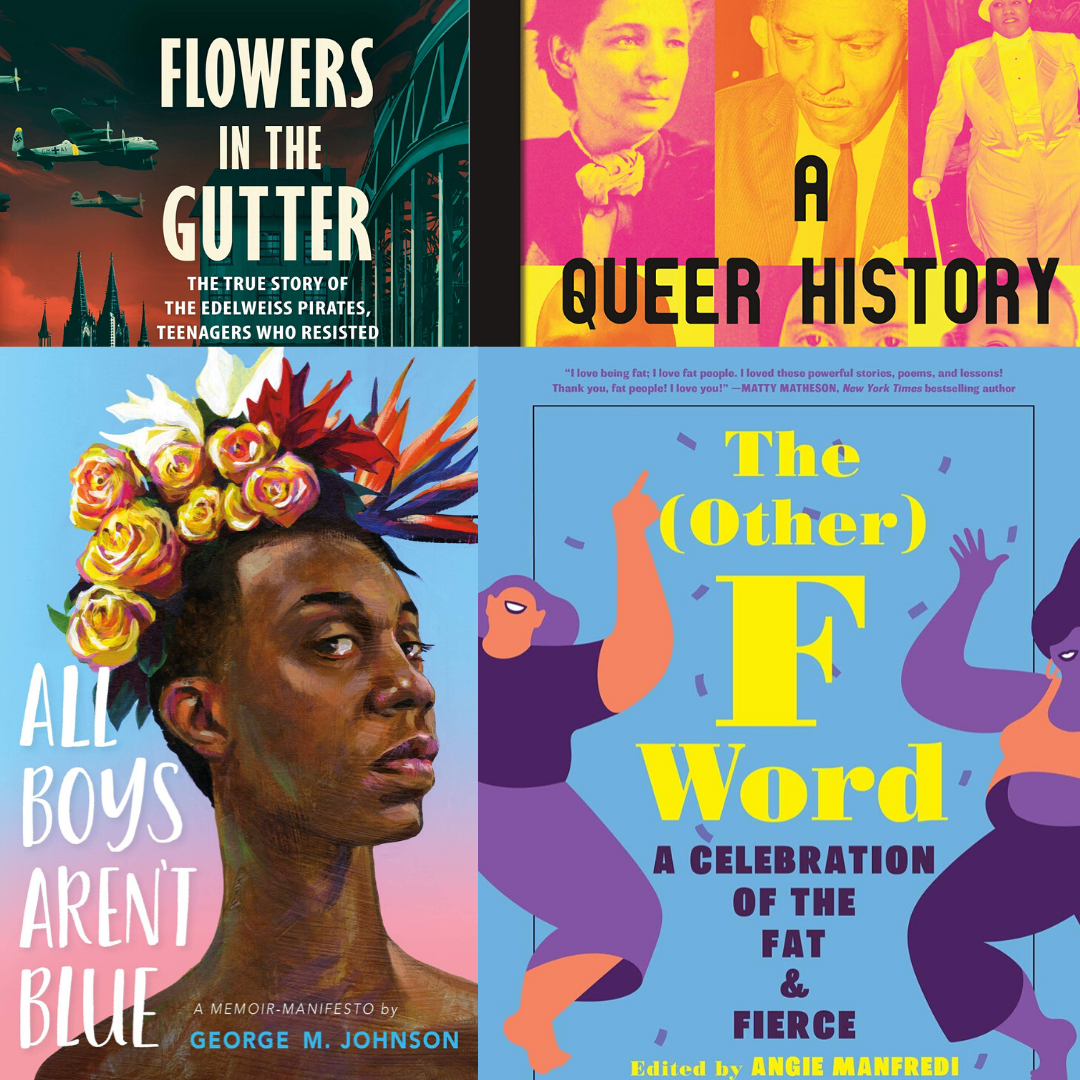

For the time being I apologized for only being able to offer fiction. My solemn promise to him was that I would put a Baker and Taylor order in as soon as I amassed better materials on his unique situation. I fell down an internet listicle rabbit hole, seeking out every narrative I could find on mental illness. In my search I also stumbled upon the fact that it was mental illness awareness month and cursed myself for not creating a themed display ahead of time. I knew that books alone couldn’t have spared him his hospitalization, but it may have saved him the conversation with me that undoubtedly drew on a well of courage that I would have lacked as a teen. My specific librarian duties ended, I put on my educator hat and began contacting people who might have him on their radar–his guidance counselor, the campus minister. With reassurance that he was doing okay for the time being I was able to focus most on the librarian side of things, knowing that he was in the care of professionals for his emotional needs.

It wasn’t the first time that a student undergoing psychiatric help had reached out to me. At the beginning of my career in the field one of the student workers I oversaw spent a similar weekend. Our relationship with each other led her guidance counselor to seek me out specifically, knowing that we interacted and saw each other on a level that other teachers might not have. All I could do for her was what she asked for–a pile of books to take with her–and what she didn’t necessarily ask for which was reassurance that she wasn’t alone. As librarians that is sometimes all that’s possible–we are not their teachers, grading them when their depression has made doing homework is impossible. We are not their guidance counselors who specifically train to ask questions and seek answers they may not be interested in giving. We are mainly collectors. Collectors of pages that bring comfort to their readers, collectors of up to date digital resources that answer questions that teens may not feel comfortable asking. Collectors of the interactions that remind us that our jobs transcend curation of content and move into the realm of thinking and feeling.

I made that display after all. May and its Mental Health Awareness didn’t end before that promising B&T box arrived full of glossy non-fiction, memoir, and graphic novels like Marbles and Hyperbole and a Half. The student never addressed me about his situation specifically but I did gesture towards it quietly during our next interaction. He still talks to me now, mainly about things of little consequence, though occasionally his original query seeps through. He asked me one day what I thought of Elliot Smith and I flashed back to a conversation I’d had with my husband where we wondered whether his depression was what made his music so beautiful. Worried that the student was thinking the same thing, that depression was somehow beautiful or a creative affliction, I told him I liked his music and wish he had gotten help so he could have kept making it. The key to helping students like this one isn’t simply in the literature we provide. It’s in these tiny moments of conversation with the overwhelming theme: You are not alone.

Please Note: This is a pseudonymous post in order to protect the identity of all involved.

See all the #MHYALit Posts Here

Filed under: #MHYALit

About Karen Jensen, MLS

Karen Jensen has been a Teen Services Librarian for almost 30 years. She created TLT in 2011 and is the co-editor of The Whole Library Handbook: Teen Services with Heather Booth (ALA Editions, 2014).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT