Coercion and Sexual Violence in LGBTQIA Lit, a guest post by Nita Tyndall

by Nita Tyndall (@NitaTyndall)

We don’t talk enough about coercion as a form of sexual assault, and we specifically don’t talk about it in regards to LGBTQ literature—narratives, as harmful as they are, of boys “wearing girls down” or talking them into sex are seen as commonplace, even acceptable and, on occasion, romantic.

We don’t think of queer couples when we think of coercion. We think of a guy pressuring a girl into sex, to keep going, to go further. This narrative is everywhere. It’s in books, it’s in movies, it’s in songs (looking at you, “Paradise By the Dashboard Light”.) Coercion in queer books becomes even more problematic, because oftentimes with power dynamics at play, characters may not only coerce their partner into sex, but into coming out.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

We do not think of two girls when we think about coercion. When we think of coercion with girls, we think outright bullying, pressuring, non-sexual, non-queer stuff. We do not think of romantic relationships, but we should.

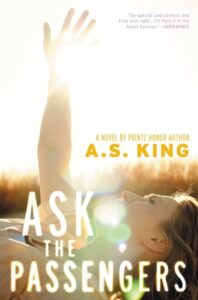

While coercion can happen between romantic relationships of any gender, I’m discussing coercion today in girl/girl relationships depicted in YA lit, most notably in A. S. King’s Ask the Passengers and Julie Anne Peters’ She Loves You, She Loves You Not. Both books show instances of coercion, though in different ways and from different points of view.

In King’s Ask the Passengers, Astrid Jones is a seventeen-year-old trying to figure out her sexuality and what it means to her. Throughout the novel she’s in a relationship with a girl named Dee Roberts, who is out.

In King’s Ask the Passengers, Astrid Jones is a seventeen-year-old trying to figure out her sexuality and what it means to her. Throughout the novel she’s in a relationship with a girl named Dee Roberts, who is out.

Astrid and Dee’s relationship is problematic from the beginning, from when readers are introduced to Dee. While this interaction is played off as a joke, it’s clear Astrid is uncomfortable with how fast Dee wants to move, and also, that this isn’t the first time this has happened:

“Now she’s laughing while she kisses me. ‘You’re not going to tell me to back off again, are you?’

‘Mmm. Hmm,” I manage while still kissing her neck, her ear. ‘Back off,’ I say. I bite her earlobe.

So far in my life, Dee is the only person who wants to totally ravish me. I have to stop her all the time.

While Dee never overtly pressures Astrid to come out, (another behavior addressed in Peters’ book), her behavior does continue.

“True.” She kisses me sloppily and it makes my insides twist up and we make out for a few minutes and everything is going great until she jams her hand into my pants and I have to stop her from going too far because I don’t want to go that far.

She slaps the car seat and says, “Dammit, Jones! Just shit or get off the pot!”

I decide Dee is now fine to drive home.

When Astrid calls her on this behavior, Dee is upset, insisting she isn’t like that or a date rapist even though she’s acknowledged previously that Astrid is scared of her.

“Is that how you want to make love to me the first time? Forcing yourself?” I’m crying. I know I’m crying about everyone who’s trying to control me, but I can’t explain that to Dee right now.

“I wouldn’t have ever done something that made you feel horrible. Jesus! You make me out like a date rapist. You know I’m not like that.”

“You were last night.”

“Stop saying that. I was not.”

“Dude, I had to stop you. If I hadn’t stopped you, what would have happened?”

Dee’s behavior isn’t viewed in a vacuum to Astrid, instead, she’s presented as another person in Astrid’s life who is trying to control her or make decisions for her. On some level this is understandable, on another, not, because it conflates sexual assault with other people in Astrid’s life who are pushy.

She chews on the inside of her cheek. “I just don’t get what the big fucking deal is. I mean, we’ve been together for over five months now. I’m pretty sure I love you!”

Wow. That was… gutsy. Not romantic, but… wow.

“Oh,” I say.

“Oh? That’s all you’re going to say?”

“No,” I say, trying to be gutsy, too. “I’m also going to say that if you—if you think you love me, then shouldn’t you treat me like you love me and respect me? And be patient with me?”

I realize that I’m saying this not just to Dee but also to my mother. And Kristina.

And Ellis. And Jeff. And maybe even myself.

Dee’s behavior does change near the end, and she ends up respecting Astrid, but the obvious power dynamic is still unnerving, and the behavior brushed off because Dee is a girl, though Astrid does comment on this at one point during the novel:

But what’s the difference between Jeff Garnet and Dee Roberts right now? Last week, Jeff’s pressing me up against his car like some big jerk and tonight Dee’s doing the same damn thing.

Astrid recognizes Jeff as a jerk, though. He isn’t redeemed. Dee is.

Coercion takes a different form in Peters’ SHE LOVES YOU SHE LOVES YOU NOT, again with a power imbalance, though this time it’s age instead of experience and the protagonist is the coercer rather than the love interest.

Coercion takes a different form in Peters’ SHE LOVES YOU SHE LOVES YOU NOT, again with a power imbalance, though this time it’s age instead of experience and the protagonist is the coercer rather than the love interest.

What’s particularly harmful in this book is Alyssa’s coercion of her ex, Sarah, is never seen as anything wrong. Apart from her mother calling her a stalker at one point, Alyssa faces no repercussions for this behavior—her dad kicks her out for being gay, but the coercion is never addressed, even though it’s clear. Alyssa is momentarily ashamed of her actions, but never is this addressed within a larger scope:

“I felt humiliated. Ashamed. Why? I’d never made Sarah do anything she didn’t want to do. She’d decided. Fifteen was old enough to decide.”

You kissed her. Looking back, she may have resisted, but it wouldn’t have mattered. You didn’t want to see. You took her in your arms and kissed her so urgently.”

Alyssa’s behavior extends into stalking her ex, as well, told through second-person passages.

“You called and called. You texted her. You IM’d, even though she asked you not to… You drove by Sarah’s house for an hour, maybe two. It was growing dark, and you drove past her house again and again, calling on your cell and texting.”

While the above behavior is not coercive, it does speak to the characterization of Alyssa, of her tendency to blatantly ignore her girlfriend’s wishes no matter the context.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

There’s another danger in Alyssa’s behavior, though also never overtly dealt with in the book, and that’s of her thoughts on another girl who she presumes to also be gay. While the character, Finn, does admit she’s queer later in the novel, Alyssa’s thoughts beforehand also ring an alarm bell:

She says, “When did you know?”

‘Know what?”

“That you were…” She can’t even say it.

“A lesbian?”

She nods slightly.

“I’ve always known. Haven’t you?”

The change in her eyes goes beyond shock. More like absolute terror.

Oh my God. She hasn’t acknowledged it yet. How could she not know?

Finn gets up and mumbles, “We should go back.”

I think, You should come out.’ (p. 109)

Coercion or pressuring someone into coming out, or assuming their sexuality, is a problem that extends beyond YA literature. The narrative of forcing someone out of the closet or insisting they’ll be happier if they are, particularly if the person doing the pressuring is already out, is extremely problematic. Choosing whether or not to come out is a heavy decision, and insisting that you know better than the person who’s coming out, or making them feel like they have no choice but to, is not only incredibly disrespectful but speaks volumes about our treatment of other queer people: That you can only be happy if you’re out, or that staying in the closet is something to be ashamed of. That other people can make that decision for you, or pressure you into making it. Upholding such narratives as okay or romantic, especially to teenagers, is awful.

We need to address coercion in YA, especially with queer relationships. We need to understand that this is not merely a heteronormative issue, that it is sometimes not as obvious as “Come on, just have sex with me.” That it can happen when both partners are the same age or the same experience level and it can happen when they are neither of those things. That it can happen when you feel like you can’t say no, because no one’s given you a handbook for what to do when your girlfriend asks you to do something you’re uncomfortable with and it’s not like she’s a rapist, right? We need to dispel the notion that the only coercion girls are capable of is bullying, that the boy with more experience is always the coercer. That if your partner is out and experienced and you aren’t then somehow you’re inadequate or not enough. That your partner gets to decide if you need to come out or not.

We need, as Dahlia Adler pointed out in her post, more positive depictions of consent. But we need depictions of coercion, too. Maybe if we have them, maybe if a teen is able to see that behavior played out on the page, they’ll recognize it, maybe they won’t ignore that gut feeling that tells them something is wrong if their partner does the same thing. Maybe they’ll stop themselves before they try to pressure their partner into sex, maybe they’ll think about the repercussions of that, of what it means.

Maybe, hopefully, they won’t think it’s acceptable or romantic anymore. Maybe they’ll realize:

No one can make decisions for you about how ready you are sexually, likewise, no one can make decisions over if you’re ready to be out or not.

Meet Nita Tyndall

Nita Tyndall (@NitaTyndall) is a tiny Southern queer with a deep love of sweet tea and very strong opinions about the best kind of barbecue (hint: it’s vinegar-based.) She attends college in North Carolina and is pursuing a degree in English. In addition to being a YA writer, she is a moderator for The Gay YA and a social media coordinator for WeNeedDiverseBooks. You can find her on tumblr at nitatyndall where she writes about YA and queer things, or on Twitter at @NitaTyndall. She is represented by Emily S. Keyes of Fuse Literary.

Nita Tyndall (@NitaTyndall) is a tiny Southern queer with a deep love of sweet tea and very strong opinions about the best kind of barbecue (hint: it’s vinegar-based.) She attends college in North Carolina and is pursuing a degree in English. In addition to being a YA writer, she is a moderator for The Gay YA and a social media coordinator for WeNeedDiverseBooks. You can find her on tumblr at nitatyndall where she writes about YA and queer things, or on Twitter at @NitaTyndall. She is represented by Emily S. Keyes of Fuse Literary.

Filed under: #SVYALit, #SVYALit Project

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

In Memorium: The Great Étienne Delessert Passes Away

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

This is so needed. So many things that should be common sense, that people should realize, but we’re just beginning to scratch the surface. Thank you!