Still Learning Every Day: HERE WE ARE editor Kelly Jensen interviews contributor Sarah McCarry

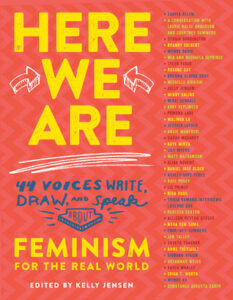

It’s the final day in our week celebrating the release of Here We Are: Feminism for the Real World edited by Kelly Jensen. Today, Kelly joins us as she interviews one of the contributors, Sarah McCarry. Be sure to visit our post from day one to enter to win a Feminist t-shirt!

“I’m Still Learning Every Day”: Sarah McCarry on Feminism

____________________

Sarah McCarry’s essay in Here We Are: Feminism for the Real World is about relationships. More specifically, her piece conveys the hard lessons that so many girls learn and experience when it comes to finding and making true friendships. Where do you let yourself stand out? Where do you make yourself fit in? And at what point do you have to confront the roles you’re playing to do one and not the other?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Here’s a short excerpt from her essay:

You make yourself superior. Superior in your silence, your lack of want. You take up no space. You quit eating and do not name aloud the hunger that rages every day in your belly. You are not like other girls. You are not like other girls (“You are not like other girls,” the boys you run with will tell you, and you will try not to let them see you preen under the glancing light of their approval). You learn their books and their language. You laugh at their jokes. You listen to their stories, sit blank-eyed on their couches while they play video games, pass them your English notes. You keep their secrets. You use the words they use about other girls in order to assure yourself that they will never use those words about you. You make yourself into nothingness, a ghost conjured into being only through the desires of boys, the rules of boys, the ideas of boys. You’re not like other girls. If you turn sideways, you are so thin, you can almost disappear. If you are good enough at this, you will be safe.

You are never quite good enough at it, as it turns out. You were never, in their company, safe.

It will take you long, lonely years, but one day you will grow tired. Tired of boys, tired of contempt, and then where will you be? All these girls around you with their stories and their lives, the solace of one another, and you will be as far away from them as an anthropologist among a foreign people, curious but unable to make contact. Have faith: you will learn.

The ways this essay talks about how we judge girls, as well as how those who identify as girls judge ourselves against other girls, is a gut-punch. It forces the reader through painful “ah ha” moments to get to those powerful, self-affirming moments. It’s an essay that defines so much of what social justice means: standing up for yourself and standing up for those who are disadvantaged by social, cultural, and political beliefs.

Kelly Jensen: If you had to pick a moment that really defined you as a feminist, where you felt like owning the term, what was that moment?

Sarah McCarry: Mmmm, that’s a good question. I can think immediately of a moment in my senior year of high school. I was in a study group with these guys from my physics class and it was important to me that they like me, that they think I was tough and cool and hot and not like other girls and all that other bullshit. They weren’t popular, exactly, but people liked them, they were rich and confident and they moved around in the world with this absolute ease that I wanted to be a part of. They sexually harassed me all the time; they harassed other girls in the class all the time; they said what, in retrospect, were horrific things about other girls in our class all the time, one of them had at that point sexually assaulted me; but I thought, then, that the way to deal with that was to be really cool. I didn’t think the issue was them or the culture that enabled them or the teacher who thought they were funny; I thought I just needed to be skinnier and meaner and more quiet and prettier but not girly and tell the right jokes and not take up any space and then I would have achieved that magical state of being one of them, of being, basically, human.

So this had been going on all year and their behavior was finally starting to trouble me in a way I couldn’t write off as my own hysteria. I will never forget a moment when we were all studying together in the café of a Barnes and Noble—this was a very small town, only goths and smokers went to the coffee shop—and they started talking about a girl in our class, saying things like she’d given dudes blow jobs to get them to do her homework for her, she was such a slut, she was trash. This girl was a thousand times smarter than all of them put together, I think she’s literally a neurosurgeon now. They were pissed because she knew better than to study with them and she did better than them by far in the class and had the audacity to be better at science than them while female and having sex with people who weren’t them. And suddenly something connected in me that had never sparked before; I understood in that moment that what they were saying was really fucked up, that what they’d done to me and to other women all year was really fucked up, that what I’d enabled them to say about other women was really fucked up, that they had never, at any point, thought of me as anything like an equal, that that was a battle I was never, ever going to win, and that I didn’t care whether or not they liked me anymore because I didn’t like a single one of them. I felt it through my whole body: I. Don’t. Care. Anymore. Just like that: I was free of them. And I stood up so fast I knocked my chair over and said, very loud, “Fuck all of you,” and walked out of there, and pretty much didn’t talk to them again after that. It was one of the more cathartic moments in my life, for sure.

But my feminism is also an organic, constantly evolving thing. For years after that moment with those dudes I still thought and said a lot of dumb things about race and class and sexuality and gender and how they operate together. I thought and said a lot of transphobic and racist and ableist and classist and just generally very stupid shit. It was a long time after that, when I had been doing social work for years, and organizing and working with a lot of incredible women of color who taught me so much—and were (god bless every one of you, you know who you are) incredibly patient and generous with me, which was a huge gift that of course I took for granted at the time—anyway, it was a long time after that before I would call my feminism anything resembling intersectional or committed to real social justice and transformation, and if my feminism is a useful tool now it’s entirely because of the work and ongoing work of women of color and trans women of color and because of the decades upon decades of work—again, in huge part by trans women of color and women of color and queer women of color—of women who came before me. I’m still learning every day.

Kelly: Your essay, while personal, is told entirely through second person. Talk about that choice and what you hope it is that readers feel as they go through the painful experiences associated with “fitting in.”

Sarah: I think that experience of internalized misogyny, of trying to transform yourself into the girl who’s not like other girls and ultimately failing—because that girl doesn’t exist, the girl who’s cool enough to be safe and respected and valued in a patriarchal system, no one has ever been that girl no matter how hard she worked or how many women she cut down or how many men approved of her—is a very common one for a lot of young (and not so young) women. I spent a long time working through shame about that experience: I wanted people who sexually assaulted me to like me, I spent a big chunk of my life putting myself into situations that I knew were physically and emotionally unsafe, I said shitty things to and about other women, and for years I thought that meant there was something fundamentally wrong with me or that I deserved what I’d been through. And of course that’s not true. I learned, working with survivors of extreme trauma, that surviving can often mean making choices that look—and often are—pretty terrible and part of moving out of trauma, of moving toward a life where trauma doesn’t define your existence, is forgiving yourself for making them in the first place. Like a lot of people, I was able to apply those lessons to others long before I realized I also got to apply them to myself. And I think the more easily you are able to be generous with yourself, the more easily you can extend that compassion to other people and see them in all their messy complicated beautiful infuriating human-ness, and hold yourself and other people accountable for your shitty choices in productive ways, and work together to move toward a world populated with the opportunities to make better ones.

The second person in the essay wasn’t a conscious choice but I think in some ways it manifested as a reminder to myself to extend the same kindness to the person I used to be as I do to other people. And for readers—I hope, wherever you’re at, that that’s useful to you.

Kelly: In what ways have you incorporated social justice/feminism into your everyday life?

Sarah: I don’t think you can separate those things, honestly. The lens of social justice isn’t something you can put away once you start looking at the world through it. It can make going to the movies a real pain in the ass, I tell you what. Once you see how power works in a system, you can’t ever unsee it again, even if you just want to watch dopey space battles on the IMAX screen.

Kelly: What are some of your favorite books and/or resources that would benefit all readers eager and curious about social justice/feminism?

Sarah: SO MANY!!!!! Mariame Kaba’s website (http://www.usprisonculture.com/blog/) is an incredible resource and so is all of the work she does—she is an extraordinary organizer who works a lot with young people around transformative justice. Everything Jenny Zhang has ever written, especially her essays and stories for Rookie. Read Audre Lorde, bell hooks, Leslie Marmon Silko, Sandra Cisneros, Gloria Anzaldúa, Maxine Hong Kingston, Sandra Cisneros, Joy Harjo, Toni Morrison (fiction and non!), June Jordan. I am a big fan of Walida Imarisha’s work, Natalie Diaz and Aracelis Girmay’s poetry, Rahawa Haile’s essays, everything Topside Press publishes… I could make this answer forty pages long, tbh. I use my twitter (@therejectionist) to flag particularly fabulous books I’m reading, you can keep an eye on that as well.

I will say that I think we have a responsibility to know our history, to know how long we’ve been fighting the exact same battles, the incredible transformative work that’s come before us; that’s something I wish I’d figured out way earlier. Read about the Black Panthers, read about ACT UP, read about Stonewall and SDS and the Combahee River Collective (http://circuitous.org/scraps/combahee.html) and AIM, read Sojourner Truth and Ida B. Wells and Angela Davis and Assata Shakur and Leslie Feinberg and David Wojnarowicz and Ronald Takaki and Cherríe Moraga. People have been thinking about—and doing a really good job of thinking about—this stuff for a long, long time.

Kelly: How can young readers and those who advocate on their behalf better prepare themselves to be actively engaged with social justice and feminism? Perhaps more specifically, how can girls help other girls so that they don’t have to learn so many of these “Girl Lessons” the hard way?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Sarah: Honestly, I think the kids are all right these days—I mean, Teen Vogue is doing some of the best, most intersectional journalism in media. This book exists. I am constantly inspired by the energy and awareness and activism of young people; I feel like I learn a lot more from them than they can possibly learn from me.

As far as people who advocate for young readers, I think one of the best things we can do is ask young people what they need most from us and then shut up and listen when they answer.

Kelly: What is the biggest thing you hope readers take away from your essay in Here We Are?

Sarah: One thing I wish I had known when I was younger was that becoming the person you want to be is a lifelong process. You don’t have to—you’re not going to—get it right straight out of the gate. If readers take away a little more compassion for themselves and for the other people around them who are struggling too, then my work here is done. For the most part, we’re all doing the best we can to thrive within a system that doesn’t want to see us flourish, and we’ll do a much better job of taking care of each other as part of a community of loving dreamers and empathetic activists than we will trying to go it on our own.

Meet Sarah McCarry

Sarah McCarry (therejectionist.com/@therejectionist) is the author of the novels All Our Pretty Songs, Dirty Wings, and About a Girl, and the editor and publisher of the chapbook series Guillotine. Her books have been nominated for the Norton Award, been a finalist for the Lambda Literary Awards, and shortlisted for the Tiptree Award, and she is the recipient of a fellowship from the MacDowell Colony. She has written for the New York Times Book Review, Glamour, Book Riot, Tor.com, and others.

Filed under: #SJYALit

About Karen Jensen, MLS

Karen Jensen has been a Teen Services Librarian for almost 30 years. She created TLT in 2011 and is the co-editor of The Whole Library Handbook: Teen Services with Heather Booth (ALA Editions, 2014).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Top 10 Posts of 2024: #10

Fuse 8 n’ Kate: Carol of the Brown King by Langston Hughes, ill. Ashley Bryan

Blake Laser | This Week’s Comics

The Seven Bills That Will Safeguard the Future of School Librarianship

ADVERTISEMENT

Hello,

Nice interview! I think its very important to read interview to get some additional knowledge. I thought and said a lot of transphobic and racist and ableist and classist and just generally very stupid shit.